December 3, 2024 Hidden history

He was what he was, with his merits and his many flaws, regardless of gender, regardless of anything.

Chevalier d’Éon, a very controversial figure who marked an era in history

Chevalier d’Éon was undoubtedly a figure who left an indelible mark on history.

Born in 1728 into an aristocratic family of Burgundian origin, he spent his early career in the civil service and then was employed by the Secret du Roi, an intelligence system (today’s equivalent of “secret services”) created by King Louis XV.

Over a period of more than two decades, Louis XV divided his diplomacy into official and secret channels, the latter designed exclusively to promote his personal interests, often at odds with official French policy.

The secret network initially numbered 32 people, led first by Cardinal Fleury and later by Charles-François de Broglie and Jean-Pierre Tercier.

Other famous agents, in addition to Chevalier d’Éon, included Pierre de Beaumarchais, Charles Théveneau de Morande, and Louis de Noailles.The Secret du Roi was officially disbanded after the death of Louis XV in 1774, but some of its agents participated in the American War of Independence.

Chevalier d’Éon finds himself one day at the court of the Empress and Autocrat of All Russia, Elizabeth I Romanov.

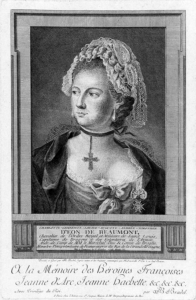

However, one important detail should be noted : in Russia, she called herself Lia de Beaumont and even became the sovereign’s maid of honor (although there is no documentary evidence to confirm this).

Returning to France in October 1760, d’Éon received a pension of 2,000 livres as a reward for his services in Russia and became a member of the dragoon corps.

In May 1761, d’Éon became its captain under Maréchal de Broglie and participated in the final stages of the Seven Years’ War, notably in the Battle of Villinghausen in July 1761.

After the death of Empress Elisabeth in January 1762, d’Éon was considered for further service in Russia, but was instead appointed secretary to the Duc de Nivernais, with a reward of 1,000 livres and the task of traveling to London to draft the peace treaty that formally ended the Seven Years’ War.

The treaty was signed in Paris on February 10, 1763, and d’Éon was awarded another 6,000 livres and received the Order of Saint-Louis on March 30, 1763, becoming Chevalier d’Éon.

Chevalier d’Éon and the French ambassador in London could not stand each other, with the former risking his job.

However, d’Éon obtained permission from the English Parliament to remain on the island as a private citizen and published what was considered a scandalous book at the time, revealing some compromising secrets of the most influential men at the French court (Lettres, mémoires et négociations particulières du chevalier d’Éon).

He threatened to publish more, even juicier ones, if the dispute was not settled.

In July 1766, Louis XV granted her a pension (perhaps as a reward for her silence) and an annuity of 12,000 livres, but refused her request for more than 100,000 livres to pay off her large debts.

D’Éon continued to work as a spy, but lived in political exile in London.

Possession of the king’s secret letters protected him from further legal action, but d’Éon could not return to France.

Perhaps for this reason, d’Éon became a Freemason in 1768 and was initiated into London’s Immortality Lodge No. 376, and later joined Tonnerre’s Lodge, Les Amis Réunis.

And so it was that the Chevalier d’Éon, exploiting his aura of “untouchable”, came to a compromise with France.

Freedom in exchange for the scandalous documents in his possession.

And it is on the meaning of “freedom” that we should dwell, for d’Éon officially returned to France as a woman.

In fact, this is nothing new.

Although she usually wore a dragon’s uniform, it was rumored in London that d’Éon was actually a woman.

A betting ring was opened on the London Stock Exchange on his true gender (today we might call it a kind of ante litteram binary option).

D’Éon was invited to participate, but declined, saying that an examination would be dishonorable regardless of the outcome.

After a year, the wager was abandoned, partly because Louis XV died in 1774, the Secret du Roi was abolished (at least officially), and d’Éon was in London trying to negotiate a return from exile.

The Chavalier d’Éon returned to France, keeping his ministerial pension, but was forced to hand over all correspondence related to the Secret du Roi.

For years, the Chevalier (as some began to call him) had constructed an advantageous and convenient narrative about his past : he claimed to have been assigned the female sex at birth and demanded that the government recognize him as such.

D’Éon claimed that he had been raised as a male because Louis d’Éon de Beaumont could only inherit from his in-laws if he had a male child.

King Louis XVI and his court granted the request, but they in turn demanded that d’Éon dress in appropriate female attire, although he was allowed to continue wearing the insignia of the Order of Saint Louis.

When the king’s offer included funds for a new wardrobe of women’s clothing, d’Éon accepted.

In 1777, after fourteen months of negotiations, d’Éon returned to France.

However, the French Revolution soon followed, and d’Éon was forced to sell all of his personal possessions, including books, jewelry, and tableware.

In 1792, d’Éon sent a letter to the French National Assembly offering to lead a division of women soldiers against the Habsburgs, but her offer was rejected.

D’Éon then competed in fencing tournaments until she was seriously wounded at Southampton in 1796.

In 1804 he was imprisoned for five months for nonpayment of debts, and shortly after leaving prison he was paralyzed after a fall.

He spent the last four years of his life in bed and died in poverty in London on May 21, 1810, at the age of 81.

The surgeon who examined d’Éon’s body stated in his post-mortem report that Chevalier had “male organs perfectly formed in all respects,” while at the same time exhibiting female characteristics, with “an unusual roundness in the formation of the limbs” and a “remarkably full bosom”.

But, frankly, this is irrelevant.

Chevalier d’Éon was what he was, with his merits and his many faults, regardless of gender and everything else.