November 1, 2024 Artistic eroticism

“Così dentro e di fuor chiara e splendente

sarete d’ogni età vero ornamento

non pur di questo secolo presente…”“Veronica Franco – vv. 25 – 28, I, Terze Rime”

Veronica Franco and her magical role as inspirational muse

These verses by Domenico Venier (dedicated to Veronica and published in the anthology “Terze Rime”) resonate like an omen, foretelling the indelible footprint that Veronica Franco will leave in the world of literature.

A female voice long ignored and still little known, especially (and paradoxically) in Italy, despite the spontaneity of her inspirational vein and the genuineness of her compositions.

Certainly, Veronica has been given the magical role of inspiring muse, source of noble emotions and sublime feelings.

But it is also true that she had to win, by proving herself worthy, the right to express her feelings and the possibility of being considered not as a literary object, but as a subject of thought and narration on a par with male poets and writers.

Sappho, whose magnificent verses were a source of inspiration even to Catullus, one of the greatest love poets of all time, was a true protagonist.

Not only did she attract the attention of the cultural world and the tastes of her time as a subject.

But also (and above all) by immortalizing his erotic pathos in unforgettable verse.

The same intensity is present in Veronica’s verses.

Women from all walks of life.

“Holy,” virgins or nuns like Enheduanna and Hildegard von Bingen.

“Married” like Christine de Pizan.

“Wretched” like prostitutes and courtesans.

As long as women remain divided into these three basic patriarchal categories, we will never be able to construct their true three-dimensional whole.

Fragmented within them, there can never be a true and solid vision of the stories of the common past.

“Women are not without history, they are not outside history.

They are in history in a special position of exclusion in which they have developed their way of life, their way of seeing, their culture”. [1]

Introduction

Narrator :

I really spent a lot of time studying Veronica’s life.

A character who was way ahead of her time.

She was not considered honorable.

To have that title, a 16th century Italian woman had to have the following six qualities :

Chastity

Silence

ModestyReticence

Sobriety

Obedience

In short, an obedient wife, a devoted mother, a good Christian.

On the contrary Veronica was the most famous courtesan of the Venetian Renaissance.

Therefore dishonorable.

The only daughter, she had taken advantage of the education she received from her three brothers to study Italian culture, Greek literature, and Roman history.

She was also said to be able to play the lute and spinet, recite and write poetry, and paint.

As a result, Veronica soon established herself as a leading figure in 16th-century literature.

Initially known among Venetian literati for her beauty and keen sense of humor, she eventually became widely known for her amorous compositions.

Indeed, in her poetry she explored her perception of Eros in a much more complex way than any of the other women in her professional circle.

In other words, her profession heightened her interest in eroticism.

Her upbringing, on the other hand, enabled her to grasp and understand its meaning in a unique way.

Veronica’s family

Veronica :

I was born in a Franca family.

We are not patricians, in fact our names do not appear in the “Golden Book of Venice”.

But we are Venetian citizens by birth.

We even have our family coat of arms (or shield), which everyone can see “at the entrance to Calle dei Franchi in the parish of Sant’Agnese in Venice” [2].

My family, together with all the other “sub-patrizi”, is registered in the “Silver Book of Venice”.

Narrator :

This group of sottopatrizi was usually employed as government bureaucrats or were members of a professional order.

Denied high government positions and the vote in the Grand Council, this caste (hereditarily defined) nevertheless occupied important positions in the “scuole grandi”, the Venetian brotherhoods and the chancery”. [3]

Veronica :

I was born in 1546, the only sister of three brothers : Girolamo, Orazio and Serafino.

My dear brother Serafino was captured by the Turks in 1570 and I do not know if he is still alive at this time. [4]

My father was Francesco Franco, son of Teodoro Franco and Luisa Federico.

Dearest Papa, I could never have trusted you to administer my estate. [5]

My mother Paola Fracassa was an “honest courtesan” like me.

Her name was listed in the “Catalogo di tutte le principal et piu honorate cortigiane di Venezia” in 1565.

Unfortunately, she died a few years later. [6]

I was married at a very young age to Dr. Paolo Panizza, a physician by profession.

My mother paid a reasonable dowry for my marriage.

We had no children.

I separated from my husband shortly after our marriage to pursue the profession of a courtesan.

At the age of 18 I became pregnant by one of my lovers.

Probably Jacomo Baballi, but I was never quite sure.

I wrote my will in October 1564, as is customary for pregnant women.

Unfortunately, one can always die in childbirth.

“I asked that [Jacomo di Baballi, a noble merchant from Ragusa (Dubrovnik)] take charge of the care and financial interests of the boy or girl who would soon be born, and as a token of [my] love, I bequeathed to him [my] diamond”. [7]

My son Achilles was born and I recovered well.

Six years later, I gave birth to my second son, Aeneas.

His father is Andrea Tron, who “married the Venetian noblewoman Beatrice da Lezze in 1569”. [8]

They had a total of six children, but unfortunately four of them died shortly after birth.

They were all born on a Friday. [9]

Narrator :

Interestingly, the movie “Dangerous Beauty, ” which focuses mainly on the period when Veronica was the protagonist of Domenico Venier’s literary salon (circa 1570-1582), does not show this part of her biography.

In “Letter Number 39” to Domenico Venier, Veronica apologizes for not being able to “fulfill [her] duty of answering [his] very kind letters” sent earlier.

Veronica :

“I have neglected to write to you, not by choice, but against my will, because of the misfortunes that have befallen me these days.

The sickness of my two little children-one after the other has died forever from fever and smallpox”. [10]

Veronica : the honest courtesan

Narrator :

At the beginning of the 16th century, Marin Seruto, a patrician and famous Venetian diarist, noted “with alarm that there were 11,654 prostitutes in a city of about 100,000 inhabitants”. [11]

Probably such a large number of women sold sex in Venice simply because it was the most important city on the west coast of the Adriatic.

A large port and a city dedicated primarily to trade.

And so those who came to the city on business, traveling without their wives, would look for a companion for the night.

But there may be another reason that has allowed prostitution to flourish in Venice over the years :

“Paradoxically, foreign travelers’ descriptions of scenes of Venetian daily life, in which the courtesan played a prominent role, often presented “the city of Venice as an example of civilization and social harmony. [12], [13]

Moreover, both the social myth of Venetian pleasure-seeking and the civic myth of Venice’s unparalleled political harmony symbolically placed the female figure in an absolutely central position.

In the sixteenth century, the female icon of Venice, depicting the republic’s unprecedented social and political harmony, “combined in a civic figure a representation of Justice or the goddess Rome with the Virgin Mary and Venus Anadiomene (the goddess Aphrodite)”. [14]

The Venetian civic myth thus openly placed the female icon at the center of Venetian social life.

At the same time, society confined the “honest” patrician woman (virgin daughter, wife, and mother) to the private sphere.

Consequently, the women who took on the visible feminine role in Venice’s public life were the “harlots” and especially the “courtesans”.

The contrast between the Virgin Mary and the goddess Aphrodite (Venus Anadiomene) was thus constantly present in the real life of 16th century Venice.

The authorities of the Serenissima Republic always tried to regulate both the life and the appearance of the “meretrice” and the “courtesan”.

In fact, patrician men were often concerned that tourists might confuse wealthy courtesans with their patrician wives.

On the other hand, they were also alarmed because, in addition to being expensive, “[the courtesans’ lavish clothing] defied male authority”[15] :

“The heavy expenditure on fine clothing could be seen as doubly assertive, drawing visual attention to individual identity and demonstrating the autonomous possession of wealth”. [16]

Therefore, churchyard laws were enacted not only for “harlots” and “courtesans,” but also for patrician women.

However, the rules for prostitutes and courtesans were stricter.

They were not allowed to wear “silk dresses” or “gold, silver, precious or even false jewelry”[17] on any part of their bodies, especially pearls.

In addition, prostitutes and courtesans were not allowed to enter (Catholic) churches during the main celebrations.

The definition of “meretrice” (a woman who sold only sexual services) and “courtesan” (or “meretrice sumptuousa”, a luxury prostitute or, as we would say today, an escort), their appearance and behavior were regulated by Venetian laws.

But “the [honored] courtesan never received a precise legal definition in the decisions of the sixteenth-century Senate”. [18]

While courtesans generally lived in splendor and were educated to a certain degree, the “honest courtesans,” the honored (privileged, wealthy, recognized), were those who “led an intellectual life, [played] music, and knew Greek and Roman literature, as well as the present, [they] mingled with thinkers, writers, and artists”. [19]

Veronica :

Ah, the lavish laws !

How else would these gentlemen suggest that the courtesans entertain them if not with our good looks and impeccable and luxurious attire ?

Of course, I add to all this my wit and my knowledge of literature.

But who would listen to a badly dressed woman, no matter how brilliant she is ?

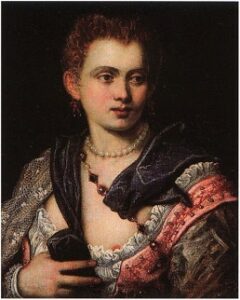

My dearest friend Tintoretto even painted me with pearls.

“I swear to you that when I saw my portrait, the work of the divine hand of [Master Tintoretto], I wondered for a while whether it was a painting or an apparition before me, a trick of the devil not to make me fall in love with myself, as happened to Narcissus (for, thank God, I do not consider myself so beautiful that I am afraid of going mad from my own magic)”. [20]

Master Tintoretto “concentrates entirely on methods of imitating – no, rather than transcending – nature, not only in what can be imitated by modeling the human figure, nude or clothed…but also in the expression of emotional states”. [21]

Yes, I am an honest courtesan like my mother.

And you will find my name in the “Catalogue of all the principal et most honorable courtesans” of 1565.

In my better days, I was admired and showered with gifts and praise by many noble Venetian patricians.

I also entertained and exchanged gifts with His Majesty King Henry III of France during his visit to Venice in 1574. [22]

But there is no such thing as a happy destiny for a courtesan.

“Even though a young woman’s destiny should be completely favorable and kind, it is a life that always turns out to be a hardship.

It is a very hard thing, contrary to human reason, to subject one’s body and labor to a slavery that is terrifying even to think about.

To make oneself prey to so many men, at the risk of being stripped, robbed, and even killed.

So that one man can one day take away everything you have worked so hard for, along with so many other dangers of injury and terrible contagious diseases.

To eat with another’s mouth, to sleep with another’s eyes, to move according to another’s will, to run, of course, to the ruin of your mind and body-what great suffering !

What riches, what luxuries, what pleasures can overcome all this ?

Believe me, of all the calamities in the world, this is the worst”. [23]

I hired Ridolfo Vannitelli to be the guardian of my son Aeneas.

At some point I realized that he and my maid Bortola had stolen some of my valuables in May 1580.

Some people can be heartless and really mean.

Vannitelli responded to my legitimate accusation by reporting me to the Venetian Inquisition.

In October of that year I was summoned to appear before the court on charges of witchcraft.

Vannitelli :

“If this witch, this public, false and deceitful prostitute is not punished, many others will begin to behave in the same way toward the Holy Catholic Church”.

Veronica :

I had to defend myself “not only against Vannitelli’s vindictive accusations of [my] “dishonest” behavior, but also against accusations of performing magical spells in [my] own home”. [24]

I confess I had taught a different way of life.

One I resisted at first but learned to embrace.I confess I became a courtesan.

Welcomed many rather than be owned by one.

I confess I embraced a whore’s freedom over a wife’s obedience.I confess I find more ecstacy in passion than in prayer.

Such passion is prayer.I confess I pray still to feel the touch of my lover’s lips.

His hands upon me, his arms enfolding me…

Such surrender has been mine.I confess I pray still to be filled and enflamed.

To melt into the dream of us, beyond this troubled place, to where we are not even ourselves.

To know that always, this is mine.

If this had not been mine – if I had lived any other way – a child to her husband’s will, my soul hardened from lack of touch and lack of love…I confess such endless days and nights would be a punishment far greater than you could ever met out.

You, all of you, you who hunger so for what I give yet cannot bear to see that kind of power in a woman.

You call God’s greatest gift – ourselves, our yearning, our need to love – you call it filth and sin and heresy…I repent there was no other way open to me.

I do not repent my life.

Narrator :

Veronica was acquitted.

Partly because of her powerful connections with patrician men and partly because of her self-defense.

But her glamorous life as a courtesan was now over.

Her financial report of 1582 shows that she was already facing financial difficulties.

This ruinous downfall was probably the result of several causes.

Her dowry and some of her other possessions were stolen: despite several official reports of theft and robbery, she was never able to recover the stolen items.

In addition, Venice was having great difficulty reviving its economy, which had been literally destroyed by the terrible Black Death epidemic (which, as we know, had a mortality rate of around 50%).

Moreover, its main benefactor Domenico Venier died precisely in 1582.

The poetess Veronica

Narrator :

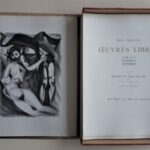

Veronica published a collection of poems called “Terze Rime” in 1575.

It was most likely a (self)published anthology thanks to the financing and sponsorship of her patron Domenico Venier.

Veronica was not the only court poetess to publish a collection of poems.

For example, Tullia D’Aragona, “another courtly poetess, also wrote a similar collection”. [25]

Veronica also edited several anthologies in honor of various men.

In her “Family Letters” and in some of her “Chapters” we read of her requests to Domenico Venier and others to contribute their poems to the collections she was working on.

“The fact that she succeeded in carrying out her plans is confirmed by the presence of editions and manuscripts in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice”. [26]

These texts suggest that she was certainly well connected in the literary circles of Venice.

From 1570 to 1580 she frequented the prestigious literary salon of Domenico Venier, where all her literary projects were published.

“Ca’ Venier was the most important meeting place for intellectuals and writers in Venice in the mid-16th century, with the possible exception of the late 1550s, when the Accademia della Fama flourished.

But the Venier family survived the end of the Accademia in 1561.” [27]

Domenico Venier was mentored by many poets and writers including several women such as Moderata Fonte, Irene di Spilimbergo, Gaspara Stampa, Tullia d’Aragona, Veronica Gambara.

Interestingly enough, none of these women are mentioned in Veronica’s writings.

Most of the intellectuals associated with Ca’ Venier rejected the poetic forms that were inspired by Petrarch‘s Dolce Stil Novo.

Under the influence of Domenico Venier, whose “interest [was] in recovering poetic models from a romantic vernacular tradition, [the poets of Ca’ Venier] turned to other forms of poetry, such as odes, madrigals, and elegies, which drew on earlier authors-not only classical elegiac poets, but also Provençal troubadours. [28]

Veronica :

I write primarily in “chapter” form, “a verse form used by 13th-century Provençal poets for literary debate.” [29]

The “chapter” is written in eleven-syllable verse and follows the three-stanza pattern of interwoven rhymes (aba, bcb, cdc, …).

The “proposition/response” mode of the “Chapter” was very popular among the members of our group, the “Ca’ Veniers.

1. “S’esser del vostro amor potessi certa A

2. per quel che mostran le parole e il volto, B

3. che spesso tengon varia alma coperta ; A

4. Se quel, che tien la mente in sé raccolto, B

5. mostrasson le vestigie esterne in guisa C

6. ch’altri non fosse spesso in frode colto, B…”

Narrator :

Veronica uses this poetic form throughout her collection of poems in “Terze Rime”.

She exchanges verses with several poets, including Domenico Venier, Marco Venier and Maffio Venier, whose “chapters” (with the exception of Maffio Venier’s poem “Veronica, Ver Unica Puttana”) appear alongside her own.

Veronica :

Marco…the magnificent Marco Venier, grandson of Domenico, respected patrician of our beloved Venice. We had…a fascinating relationship.

Narrator :

This poetic dialog with Marco Venier, supported by some other “chapters” in “Third Rhymes”, probably inspired the screenwriter of the movie “Dangerous Beauty”.

The romantic story between Veronica and Marco is one of the possible interpretations of his love poems.

It would be very nice if the end of Veronica’s real life was as happy as the one in the movie “Dangerous Beauty”.

The final images – a gondola in which the two lovers passionately embrace and a background of Venetian canals and palaces – foreshadow a future in which Veronica and Marco would be lovers forever.

As in a beautiful fairy tale.

Margaret Rosenthal ends her book “The Honest Courtesan” in the same way, describing in the last chapter a “romantic” literary analysis of Veronica’s last poem “Chapter 25”.

A praise of the Villa Fume in the Verona countryside, where she stayed during the years of the Black Death.

However, Veronica’s life did not end in the arms of her beloved or in the beautiful countryside.

In fact, we do not know exactly where, how and in what condition she died in 1591.

Since she had been having financial problems for nine years prior to her death (as evidenced by her 1582 tax return), she most likely died in much less pleasant surroundings than those described by both “Dangerous Beauty” and Margaret Rosenthal.

Like most courtesans who had suddenly lost all their possessions, Veronica Franco probably died in a poor district of prostitutes in Venice, forgotten by the powerful patricians who, on the contrary, had admired her at the height of her career as an honored courtesan of Venice.

“No poem, no letter was found when her death was registered.

Only the official in charge of death records in Venice entered the event in his register: … 1591, July 22. Mrs. Veronica Franco, aged forty-five, died of fever on July 20. Buried in the church of Saint Moisé”. [30]

Veronica and the women

Narrator :

“Although [Veronica] was necessarily an individualist who went her own way, she also thought of women in a “we plural” way.

As a courtesan, she wrote about the situation of the women who shared her profession, and in addition to this topic, she spoke about the situation of women in general”. [31]

Already in her first two testaments, we can read of her concern for poor young women who could not afford a dowry sufficient for a decent marriage.

Veronica :

My first concern has always been to provide for my family.

But I never forgot other women more unfortunate than myself.

I would secure a dowry for this or that girl, or give money to the Zittelle House, “a charitable institution founded to protect poor, unmarried girls in order to prevent their loss of chastity and consequent loss of the possibility of marriage. [32]

Poor mothers often see the only way out of their misery in turning their young daughters into courtesans.

Oh, I have written many times, I have begged these naive mothers “not to destroy with one blow [their] souls and reputations along with [their daughters]…[They] talk of happiness, but [I keep telling them] there is nothing worse than giving up happiness, which can more easily bring trouble than benefit.

Wise people, in order not to be deceived, rely on what they have within themselves and what they can make of themselves.” [33]

Oh, the miserable life of a courtesan, the dangers, the injustices, the false accusations…

“Ver unica” e ‘l restante mi chiamaste,

alludendo a Veronica mio nome,

ed al vostro discorso mi biasmaste ;

ma al mio dizionario io non so come

“unica” alcuna cosa propriamente

in mala parte ed in biasmar si nome.

…….

Quella di cui la fama è gloriosa,

e che in bellezza ed in valor eccelle,

senza par di gran lunga virtuosa,

“unica” a gran ragion vien che s’appelle

……..

L’”unico” in lode e in pregio vien esposto

Da chi s’intende;………” (XVI, vv. 140 – 156)[34]

Narrator :

When Veronica wrote the famous line, “When we too are armed and trained,” she was certainly not referring to physical ability.

She was obviously alluding to women’s education, which did not exist systematically in her time.

We do not know if she was formally educated (there were a few rare schools for girls).

It is more likely that her culture was a mosaic of her brothers’ lessons, her mother’s teachings (as an honored courtesan, she must have had some knowledge of literature, Greek, and Latin), and, finally, what she had learned in Domenico Venier’s literary circle.

Sixteenth-century Italy was certainly fertile ground for the various women from all walks of life who later became known as writers and poets.

Two main factors contributed to the positive attitude of the society at that time towards women and their literary works.

Following the example and ideas of an early 16th century humanist (Pietro Bembo), men of letters began to write in Italian rather than Latin.

Widespread literary production then began to flourish in the Tuscan and Venetian dialects.

In this way, many more women (who had not been educated and therefore did not know Latin) were able to read the new literary productions.

And in the same period, also thanks to the discovery and spread of printing, copies of literary texts became increasingly available.

On the other hand, in the same period, some Renaissance humanists began to recognize women as individuals with “the same spiritual and mental capacities as men and [admitted that] women too can excel in wisdom and action. Men and women possess the same essence”. [35]

Conclusion

Narrator :

Veronica Franco’s poems in the “Terze Rime” and her letters in the “Familiar Letters to Various Persons” represent the “perfect story” [36] of the courtesan and poetess, a single woman whose life was woven into the fabric of Venice in the second half of the sixteenth century.

She dared to speak out when women were expected to remain silent.

She managed to lead an intellectual and public life when women were confined to the domestic sphere.

And she openly celebrated female sexuality when chastity was one of the highest virtues women could attain.

In short, she used the same tools that men used to advance the cause of women.

To defend them against misogynistic attacks and to expand the understanding of women as individuals who possess not only bodies but also minds.

The fusion of reason and sensuality in Veronica’s writings is what fascinates me most.

I think this fusion is an extremely important jewel in the tapestry of women’s vision.

Notes

[1] Sigrid Weigel, Double Focus : On the History of Women’s Writing in Feminist Aesthetics (edited by Gisela Ecker, translated from the German by Harriet Anderson), Beacon Press, Boston, 1985, p.61

[2] According to the Italian scholar Guiseppe Tassini, this coat of arms still exists in the position citied. The quotation is from Margaret F. Rosenthal, The Honest Courtesan : Veronica Franco, citizen and writer in sixteenth-century Venice , University of Chicago Press, 1992, p. 66

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., p. 78-79

[5] Margaret Rosenthal reports that in Veronica’s second will, dated November 1, 1570, “despite his claim to be her ‘dearest father,’ the way he gives him his money makes it seem as if he does not trust him. (p. 81) But Rosenthal and Veronica herself (according to Rosenthal) do not provide the reason for this distrust. Perhaps he was a drunk, as the movie about Veronica, “Dangerous Beauty” (directed by Marshall Herskowitz, 1997), informs us.

[6] At the time of Veronica’s First Will on August 10, 1564, her mother was still alive. She died some time before Veronica’s Second Will, written on November 1, 1570.

[7] Irma B. Jaffe, Shinning Eyes, Cruel Fortune : The Lives and Loves of Italian Renaissance Women Poets, Fordham University Press, New York, 2002, p. 341

[8] Rosenthal, p. 80.

[9] From Veronica’s testimony at the trial of the Inquisition in 1580, as reported by Rosenthal in The Honest Courtesan , p. 83

[10] Veronica Franco, Familiar Letters to Various People (1580), edited and translated by Ann Rosalind Jones and Margaret F. Rosenthal, Veronica Franco : Selected Poems and Letters, University of Chicago Press, 1998, pp. 23-46

[11] Rosenthal, p. 11

[12] Ibid, p. 12

[13] Sixteenth-century Venice was an independent republic, organized as a series of magistracies and councils, ruled by the Doge, who was elected for life by the Grand Council, composed of 26 elected patricians. The next most important governing body was the Venetian Senate with 150-200 members elected by all the patricians of Venice.

[14] Rosenthal, pp. 12-13

[15] Ibid, p. 69

[16] Ibid, p. 69 Rosenthal quoting Chojnacki

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid, p. 67

[19] Ann Rosalind Jones and Margaret F. Rosenthal, “Introduction : The Honorored Courtesan” in Veronica Franco: Selected Poems and Letters , University of Chicago Press, 1998, p. 3

[20] “Letter 21” in Rosenthal & Jones, p. 37.

[21] Ibid.

[22] As he informs us in his publication of “Familiar Letters to Various People” in 1580, Jones & Rosenthal, p. 24

[23] “Letter 22” in Jones & Rosenthal, p. 39

[24] In the movie “Dangerous Beauty”, the accusation of witchcraft is not mentioned; the screenwriter focused only on “her” dishonest “behavior”. However, Veronica’s witty defense is clearly presented in this film, as well as in Rosenthal’s interpretation of the Italian transcripts of the trial.

[25] Jones & Rosenthal, p. 13

[26] Ibid, p. 89

[27] Ibid, p. 211

[28] Jones & Rosenthal, p. 7

[29] Jaffe, p. 364

[30] Jones & Rosenthal, p. 3

[31] Ibid, p. 38

[32] “Letter 22” in Jaffe, p. 340.

[33] Third Rime,

[34] Margaret L. King and Albert Rabil, Jr., “The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe : introduction to the series,” University of Chicago Press, 1998, p. xix

[35] Quoted in Jaffe, pp. 25-26

[36] Cites Francis Bacon for the term “perfect history.”